Sylvia Earle: Her Deepness

Sylvia Earle is an American marine biologist, oceanographer, explorer, author, and lecturer.

The world-renowned marine biology expert is known for her marine algae research and her efforts to raise awareness of the threats caused by overfishing and pollution.

Earle has dedicated her career to protecting the Earth's oceans and is internationally known as an ambassador-at-large to the sea.

The ocean is a temptress, enticing us into its inexplicable depth.

But if there’s one oceanographer brave enough to chart its waters, it’s Sylvia Earle.

Known to many as “Her Deepness,” Earle is perhaps one of the world’s best-known female marine scientists.

Born 30 August 1935 in Gibbstown, New Jersey, USA, Earle is an American marine biologist and explorer known for her research on marine algae and her books and documentaries designed to bring awareness to the threats that overfishing and pollution pose to our oceans.

The second of three children born to electrical engineer Lewis Reade Earle and his wife, Alice Freas Richie, Earle spent much of her early life on a small farm near Camden, New Jersey.

There, she developed a deep appreciation and love for nature.

From a young age, her parents taught her to respect the wild and not to be afraid of the unknown.

At the age of 12, her family moved to Dunedin, Florida, where the family’s waterfront property allowed Earle the opportunity to explore and learn about sea life.

Her love for the ocean would eventually pave the way for her career.

She completed her thesis work on algae in the Gulf of Mexico before going on to complete a PhD in 1966. After earning her master’s degree, Earle took time off to marry and begin a family but remained active in marine exploration.

No water, no life. No blue, no green.

– Sylvia Earle

In 1964, she left home for six weeks to join a National Science Foundation expedition in the Indian Ocean.

Her children were only two and four at the time.

In 1969, she published her dissertation Phaeophyta of the Eastern Gulf of Mexico, which required that she collect over 20,000 samples of algae.

Never before had a marine scientist made such an extensive first-hand study of aquatic plant life.

Since then, she has made it a mission to document every plant species that can be found in the Gulf of Mexico.

Earle’s career eventually allowed her to attend Harvard as a research fellow and then become resident directorship of the Cape Haze Marine Laboratory in Florida.

In 1968, when she was four months pregnant, Earle travelled a hundred feet below the waters of the Bahamas in the submersible Deep Diver.

But Earle’s research didn’t stop there.

In 1969 she participated in the Tektike Project.

Sponsored by the US Navy, the Department of the Interior and NASA, the venture allowed teams of scientists to live for weeks in an enclosed habitat on the ocean floor 100 feet below the surface, off the Virgin Islands.

Earle had already spent thousands of research hours underwater but went on to create and lead Tektite II, Mission 6, an all-female research expedition, earning the record title for the first all-female aquanaut research team.

Additionally, she continued to go on marine expeditions throughout the world, usually serving as their chief scientist.

But it wasn’t just Earle’s research that made her a recognizable face in the scientific community. Earle also began collaborating with undersea photographer Al Giddings.

Together, they explored a battleship graveyard in the South Pacific and followed great sperm whales in a series of expeditions that were featured in the documentary Gentle Giants of the Pacific (1980).

Earle and Giddings worked together on her 1980 book, Exploring the Deep Frontier, which detailed her experience walking untethered on the sea floor at a lower depth than any person before her, earning her the record title for the deepest untethered sea walk (female).

On 19 September 1979, Earle wore a pressurized suite and was carried to a depth of 381 metres (1,250 feet), where she separated from the submersible and discovered the sea floor for two and a half hours.

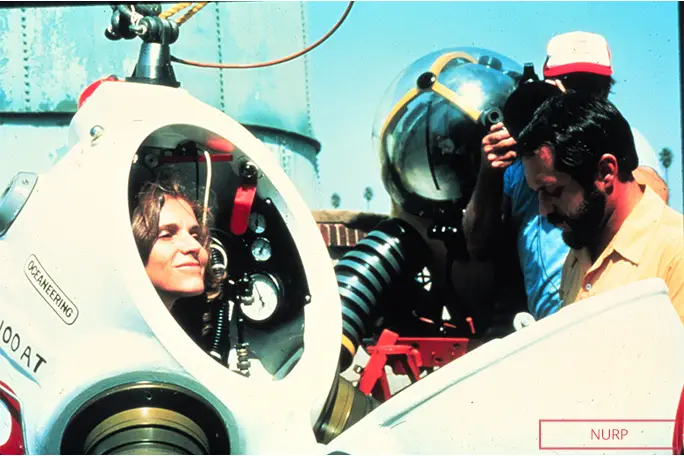

In the 1980s, Earle teamed up with engineer Graham Hawkes (her third husband) and founded the companies Deep Ocean Engineering and Deep Ocean Technology where they designed and built underwater vehicles that helped scientists work at extraordinary depths.

Together they designed the submersible Deep Rover, a vehicle capable of reaching depths of 914 metres (3,000 feet) beneath the surface of the ocean.

In fact, in 1985, Earle achieved the deepest solo descent by submersible (female) by descending 1,000 metres (3,280 feet) aboard the Deep Rover submersible, off San Clemente Island, California, USA.

Throughout her career, Earle has made many important scientific contributions that have helped us better understand the deep-sea ecosystem and just how important it is to protect it. Earle’s pioneering research on marine ecosystems also saw her named the first TIME Magazine Hero of the Planet in 1998.

With every drop of water you drink, every breath you take, you're connected to the sea.

– Sylvia Earle

To date, Earle has spent over 7,000 hours underwater exploring the ocean and analysing its inhabitants.

Through her experiences and scientific research, Earle has become a leader in ocean conservation and has worked vigorously to raise awareness about the dangers the ocean faces.

At 87, she remains a passionate ocean explorer and campaigner for the seas and still dives at least once a month.

Most recently, Earle led the Google Ocean Advisory Council, a team of 30 marine scientists providing content and scientific oversight for the “Ocean in Google Earth.”

She has led over 80 expeditions and has received more than 100 national and international honours, including the 2009 TED prize for her proposal to create a global network of marine protected areas.

Today, Earle continues to spread her message throughout the globe via lectures and documentaries, reminding people that the continued decline in the health of our ocean is not inevitable, it’s preventable.