Oldest written customer complaint

- Who

- Complaint tablet to Ea-nasir

- What

- 3767 year(s)

- Where

- Iraq (Babylon )

- When

- 1750 BCE

The oldest written customer complaint is the "Complaint tablet to Ea-nasir" and is 3767 years old, acquired by the British Museum (UK) in London, UK, in 1953.

The tablet was discovered in the ancient city of Ur (southern Iraq). The tablet describes the complaint to the merchant, named Ea-Nasir, from a customer, named Nanni. The complaint is in relation to the wrong grade of copper being delivered to Nanni and suggests the feud between buyer and seller had been going on for a long time.

There is a translation of the tablet in Letters from Mesopotamia: Official, Business and Private Letters on Clay Tablets from Two Millenni by Assyriologist A. Leo Oppenheim. The translation states the following:

"Tell Ea-nasir: Nanni sends the following message:

When you came, you said to me as follows : “I will give Gimil-Sin (when he comes) fine quality copper ingots.” You left then but you did not do what you promised me. You put ingots which were not good before my messenger (Sit-Sin) and said: “If you want to take them, take them; if you do not want to take them, go away!”

What do you take me for, that you treat somebody like me with such contempt? I have sent as messengers gentlemen like ourselves to collect the bag with my money (deposited with you) but you have treated me with contempt by sending them back to me empty-handed several times, and that through enemy territory. Is there anyone among the merchants who trade with Telmun who has treated me in this way? You alone treat my messenger with contempt! On account of that one (trifling) mina of silver which I owe(?) you, you feel free to speak in such a way, while I have given to the palace on your behalf 1,080 pounds of copper, and umi-abum has likewise given 1,080 pounds of copper, apart from what we both have had written on a sealed tablet to be kept in the temple of Samas.

How have you treated me for that copper? You have withheld my money bag from me in enemy territory; it is now up to you to restore (my money) to me in full. Take cognizance that (from now on) I will not accept here any copper from you that is not of fine quality. I shall (from now on) select and take the ingots individually in my own yard, and I shall exercise against you my right of rejection because you have treated me with contempt.”

Writing Materials and Methods of the Past

We’re used to communicating with each other instantly, via phone calls, text messages, or on social media. Early civilizations, of course, had no such advantages. Our earliest, pre-lingual ancestors would have expressed themselves by the tone of their utterances, perhaps supplemented by gestures; conveying information over a distance – for example, in times of battle or to send warnings – was not possible until the development of tools such as drums and horns. Visual messaging – smoke signals and fires – fulfilled a similar purpose.

Long before written records existed, fundamental information about a tribe or people was conveyed through oral tradition; folklore could be transmitted down the generations through song, dance and art. Eventually, perhaps 40,000 years ago, a pictorial language emerged – carvings on rock surfaces or trees, known as pictograms and petroglyphs.

> These petroglyphs, some dating back 2,000 years, are located at Newspaper Rock State Historic Monument in Utah, USA. They were carved by several different Indigenous peoples; the Navajo name for them is “Tse’ Hone” (“a rock that tells a story”).

> These petroglyphs, some dating back 2,000 years, are located at Newspaper Rock State Historic Monument in Utah, USA. They were carved by several different Indigenous peoples; the Navajo name for them is “Tse’ Hone” (“a rock that tells a story”).

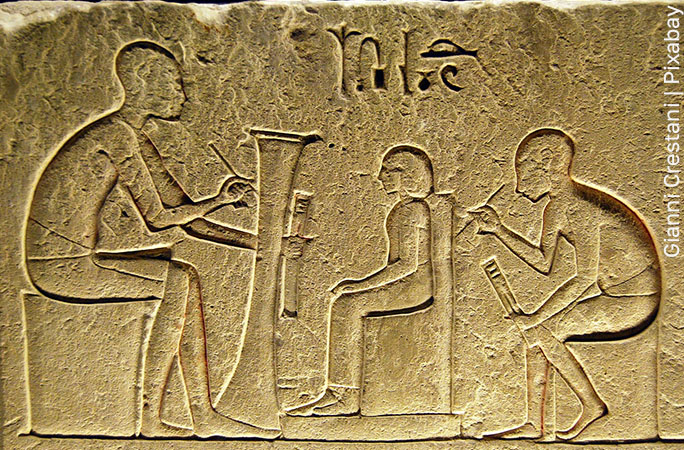

Historians believe that the oldest known form of writing – “cuneiform” – was developed around 3500 BCE by Sumerian scribes in Uruk, a settlement in Mesopotamia (now southern Iraq) that was one of the earliest cities. The scribes chronicled commercial transactions and property ownership, legal documents and religious texts, by making indentations on clay tablets with styluses made from reeds. The marks were wedge-shaped (“cuneus” in Latin), hence the name of the script. Once dried, or fired, the malleable clay hardened, becoming durable enough to allow the tablet bearing the oldest customer complaint to survive into the 21st century. Scribes chose their material based on its perceived importance; royal inscriptions might be engraved on precious metal, or stone.

The first complex written communications system emerged in ancient Egypt a few hundred years later, in the form of pictorial symbols known as “hieroglyphics”. (In around 2000 BCE, the earliest alphabet emerged here too.) They adorned the walls of temples and monuments, and were written on a thick, coarse type of paper known as “papyrus”, made from the pith of the eponymous plant. Lighter and more portable than clay tablets, papyrus scrolls enabled information to be carried and disseminated over wide areas.

> A scribe’s role was vital to the administration of ancient societies, and therefore a prestigious position.

> A scribe’s role was vital to the administration of ancient societies, and therefore a prestigious position.

The Historical Context of Written Complaints

In the ancient world, written records were invaluable for trade and commerce. (Merchants kept ledgers in part to protect themselves against legal challenges.) They were also crucial for establishing and enforcing laws.

One such set of regulations was the Babylonian Code of Hammurabi, which dates from 1754 BCE. It contains more than 280 laws; No.107 stipulates that any merchant found to have cheated the agent who sells his goods is liable to pay that agent an amount six times that of the original sum. And law No.7 demonstrates that when it came to commercial transactions, having a witness, or a written contract, could literally be a life-saver:

If any one buy from the son or the slave of another man, without witnesses or a contract, silver or gold, a male or female slave, an ox or a sheep, an ass or anything, or if he take it in charge, he is considered a thief and shall be put to death.

Common Themes in Ancient Customer Complaints

Complaining seems to be one of the qualities that bind us together as human beings. A quick glance at the internet suggests that many of us appear to be happiest when we’re annoyed.

Consumer complaints haven’t changed that much over the millennia. Delayed delivery, damaged or insufficient goods, quibbles over price, breach of trust, inaccurately described products, slow (or no) response from the supplier – the same issues that pepper online reviews and comments today also rankled with our forebears.

The British Museum houses several such missives. One is an ancient Egyptian petition from c. 1110 BCE, wherein a customer expresses frustration at being overcharged for a service. Another, in the form of a fifth-century mosaic from Antioch (today Antakya, in southern Turkey), portrays an aggrieved customer accusingly holding a defective jug in front of the seller.

The museum is also home to the oldest written customer complaint, dating from 1750 BCE. Written in cuneiform on a clay tablet, it was discovered in the ancient city of Ur, in present-day southern Iraq. The message is addressed to Ea-nāṣir, a merchant, from a customer named Nanni, who has received an inferior grade of copper ore; its tone suggests that there was a long-running feud between the two men.

A translation of the tablet (by A Leo Oppenheim, an Assyriologist) reads:

Tell Ea-nāṣir: Nanni sends the following message:

When you came, you said to me as follows: “I will give Gimil-Sin (when he comes) fine quality copper ingots.” You left then but you did not do what you promised me. You put ingots which were not good before my messenger (Sit-Sin) and said: “If you want to take them, take them; if you do not want to take them, go away!”

What do you take me for, that you treat somebody like me with such contempt? I have sent as messengers gentlemen like ourselves to collect the bag with my money (deposited with you) but you have treated me with contempt by sending them back to me empty-handed several times, and that through enemy territory. Is there anyone among the merchants who trade with Telmun who has treated me in this way? You alone treat my messenger with contempt! On account of that one (trifling) mina of silver which I owe(?) you, you feel free to speak in such a way, while I have given to the palace on your behalf 1,080 pounds of copper, and umi-abum has likewise given 1,080 pounds of copper, apart from what we both have had written on a sealed tablet to be kept in the temple of Samas.

How have you treated me for that copper? You have withheld my money bag from me in enemy territory; it is now up to you to restore (my money) to me in full. Take cognizance that (from now on) I will not accept here any copper from you that is not of fine quality. I shall (from now on) select and take the ingots individually in my own yard, and I shall exercise against you my right of rejection because you have treated me with contempt.”

And Nanni was not alone. Similar complaints from other customers were uncovered in Ea-nāṣir’s house, including multiple messages from two correspondents named Imgur-Sin and Arbituram asking the merchant to send good-quality copper to a third man (implying that the merchant had supplied sub-standard ore in the past), and an anonymous customer seeking damages because he had received less copper than expected.

Were he in business today, Ea-nāṣir might expect one-star ratings. At best.

Consumer dissatisfaction was by no means restricted to the general public, though. In the second century BCE, Tushratta – the king of Mitanni (an Indo-Iranian empire) – complained to the Egyptian pharaoh Akhenaten that rather than receiving solid-gold statues (as agreed with Akhenaten’s father, Amenhotep III), he had been palmed off with “[gold-] plated ones of wood”. And the quantities were a let-down too: “Nor have you sent me the goods that your father was going to send me, but you have reduced (them) greatly.” Tushratta probably waited a long time for the expected goods, if he ever got them; he wrote several times on the subject, and even petitioned the queen mother.

The Legacy of Early Consumer Feedback in History

Nanni’s 4,000-year-old grievance offers a fascinating insight into the Mesopotamian economy during the Bronze Age. Ur – his home city – had easy access to the Persian Gulf and became a trading hub, part of a widespread network that operated within the Mediterranean region and stretched eastwards to India.

Copper was a highly valued commodity, used for tools, various vessels and cutlery, and smelted with tin to make bronze. The city did not have readily available supplies of metal, however. Ur’s traders and merchants had to buy copper ore from the kingdom of Dilmun (centred on what is now Bahrain Island), then ship the cargo some 960 km (600 miles) northwards up the Gulf to their city.

> Today, Ur’s ziggurat towers over a desert landscape. But when the imposing structure was built, in around 2100 BCE, the city stood in fertile marshes at the confluence of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, and was a vital cog in the wheels of Eurasian trade.

> Today, Ur’s ziggurat towers over a desert landscape. But when the imposing structure was built, in around 2100 BCE, the city stood in fertile marshes at the confluence of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, and was a vital cog in the wheels of Eurasian trade.

This was a costly and risky business, so merchants collaborated to raise funds for the expeditions. Once the copper was in Ur, they sold it, split the profits and paid taxes to the royal palace.

Much later, during the period of colonial expansion by European powers from the 16th to 18th centuries, national governments took on a quasi-mercantile role and began to regulate trade themselves. This provided them with lucrative revenue streams from taxes on products. To maximize their monopoly, they also penalized any of their colonies that bought from sources other than officially sanctioned trading companies. This led to widespread resentment on the part of the colonials – whom we might think of as aggrieved customers beholden to a particularly inflexible supplier. In this context, a “customer complaint” might have far-reaching consequences…

During the 18th century, colonists in North America used pamphlets and newspaper articles to complain about the taxes they were being forced to pay to the British government on imported goods such as stamps, paper and tea. They argued that these were unconstitutional, as they had been denied any meaningful voice in the British parliament – an argument summed up in the famous line “No taxation without representation”. Those complaints went unheeded, however, and helped spark a revolutionary uprising that led to the American War of Independence.

Had the colonists’ grievances been addressed in a timely and satisfactory manner, how different history might have been.