“No barriers” mindset of blind adventurer helps secure his place as a GWR ICON

Erik Weihenmayer (USA) was diagnosed with juvenile retinoschisis as a toddler and, by the age of 14, the condition had left him totally blind. It’s not the typical start to the story of someone that will go on to become a record-breaking mountaineer – but then Erik is far from a typical person in many ways.

Erik at the summit of Everest (aka Chomolungma or Sagarmatha) in 2001. Credit: Luis Benitez

Erik at the summit of Everest (aka Chomolungma or Sagarmatha) in 2001. Credit: Luis Benitez

As the first blind person to climb Mount Everest (in 2001) on his way to becoming, a year later and again in 2008, the first blind person to climb the Seven Summits (once he’d scaled the highest mountain on all seven continents), his records reflect his both trailblazing and headstrong spirit. Though he acknowledges that, over the years, it’s sometimes been a battle between heart and head when it comes to how far to push himself.

“There’s this saying,” Erik expounded in an exclusive interview with GWR. “‘There are old mountaineers and bold mountaineers. But there aren’t old, bold mountaineers.’ In reality, you sometimes have to be bold as a mountaineer, but if you’re always bold, then you’re not gonna be around for very long! So you have to take strategic risks.”

![]()

In the GWR 2026 edition, Erik is celebrated as one of the latest GWR ICON inductees. To mark this special accolade, GWR presented the pioneering explorer with a bespoke Braille certificate – a milestone first for GWR – at his home in Colorado.

When I could still see as a young boy, I remember being spellbound by the incredible achievements sprawled across the pages of the Guinness Book of World Records. Now 50 years later it’s hard to imagine that my achievements would be listed among them, and even more so that they would honour me as an ICON! - Erik Weihenmayer on being inducted as a GWR ICON

As a youngster Erik was always into sports, particularly basketball and baseball. But as his sight steadily declined, it dawned on him – with a mature pragmatism that belied his limited years – that certain hobbies he had enjoyed were no longer going to be feasible.

While it might have been easy to slip into a spiral of negativity at this point, Erik recognized that figuratively the ball was very much still in his court. He knew, even then, that it wasn’t a case of giving up but adapting. Now aged 57 and still taking on new challenges and adventures to this day, this remains the fundamental ethos he lives by.

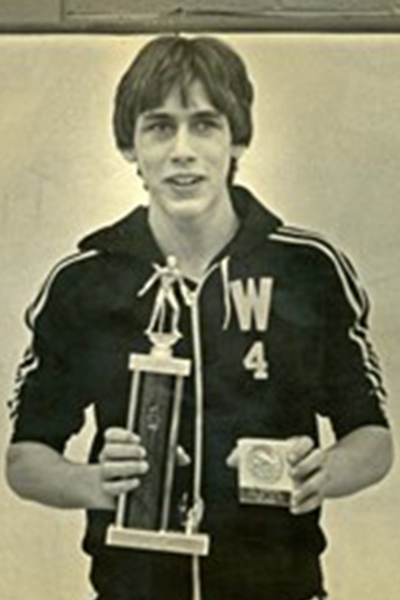

Erik won numerous trophies during his time competing in wrestling at high school

This open-minded approach as a teenager led Erik to the world of high-school wrestling. Owing to its tactile nature, this was a pursuit in which Erik could not only get by, but truly excel, regardless of his sight loss. He found success on the mat not just in local leagues but also at state level and even in national competitions.

The sport would become a lifelong passion, as even after he stopped competing, Erik would go on to coach others. In 1996, the National Wrestling Hall of Fame chose him to receive that year’s Medal of Courage, an annual award given to wrestlers who are deemed to have “overcome seemingly insurmountable challenges”.

Grand adventures in the great outdoors were not particularly on his radar for much of Erik’s early life, but two things culminated in his teens that changed that. Firstly, when he was aged 15, his mother tragically died in a car accident. He explains how this shattering event brought the Weihenmayer family closer together, often through embarking on trekking vacations in some far-flung and challenging locations.

“My dad wanted to keep my brothers and I close. He’d take us on these crazy treks, which is where my experience with mountains began.

“He took us to the Inca Trail in Peru and we went to Pakistan and hiked in the Karakorams, over the Baltoro Glacier and up to these remote villages. We went to Papua New Guinea, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan and on and on. My dad treated us to these incredible adventures.”

Erik aged 15 with his first guide dog, German shepherd Wizard

Given what he would go on to achieve, tackling the world’s highest mountains and many more besides, it might come as a surprise to learn that he initially hated hiking.

“I hated it because it was so hard,” he revealed. “As a blind person, my dad would grab the back of my shirt or the waistband of my shorts, and he’d try to steer me up these trails.

“I hadn't discovered trekking poles yet, so I just had a cane, which would often bend and break, and I’d fall over a lot. But I wanted to be with my family. It sucked, but I toughed it out, until I figured out using trekking poles and somebody walking in front of me wearing a bell so I could follow the jingling.”

As often is the case, a teacher also played a vital role in igniting a spark in him. “As a freshman, I had a Braille teacher who was trying to teach me how to read,” Erik recalls. “She’d try to find articles to excite me and get me interested. Some of these were about people skiing across Antarctica, such as the race between Robert Falcon Scott and Roald Amundsen [leader of the first people to reach the South Pole, in 1911]. And I was like, wow, that’s fascinating.

“Then she brailled out an article about Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay [the first people to summit Everest, in 1953] and I just remember being blown away. These were insane pioneers, you know? I was always impressed by people like that, but at the time I didn’t put myself in that camp.”

Erik’s perception of his capabilities was about to change, however, when rock climbing entered his life, which proved to be a game-changer. Because so much focus in this activity is on the hands and feet, he notes that he actually found climbing easier than hiking.

“I remember that first time rock climbing in North Conway, New Hampshire. It was through The Carroll Center for the Blind, which is a rehabilitation centre for blind people. I was learning how to echolocate, which involves using sound to hear and perceive your surroundings.

“I got to the top of this rock face, some 100 ft [30 m] up, and I was sitting on this little ledge. I could hear the whole expanse of the valley below me, and it was absolutely beautiful. I just wanted to do it more, so I kept looking for opportunities.

“Things kind of escalated after I graduated and took a job as a teacher in Phoenix. There, I joined the Arizona Mountaineering Club and met a substitute teacher called Sam. We’d go climbing together. He was the one who initially said, ‘We’re pretty good at this, we should do something bigger.’ I was thinking he was talking about maybe a 200-ft rock face, but then he said, ‘How about Denali?’ [Mount Denali, aka McKinley, in Alaska, USA, is North America’s highest mountain at 20,310 ft (6,190 m) above sea level.]

Maybe I’m getting too deep here, but when you go blind, it’s like the scariest thought that you’re never gonna have adventure in your life again. You’re never gonna have excitement. You’re gonna always be on the sidelines listening to life go by. So to be in my 20s, and thinking there’s a prospect I could travel around the world scaling the biggest mountains was mindblowing - Erik Weihenmayer

That sowed the seed for taking on the Seven Summits – an idea that once it had taken root became difficult to dislodge. After a 19-day slog, he and Sam reached the top of Denali on 27 June 1995.

Erik on a return visit to Denali in 1999. Credit: Jamie Bloomquist

From that point, Erik was hooked. With one of the Seven Summits now under his belt, he set his mind to seeing the prestigious alpinism challenge through to its completion – something he would achieve seven years later.

Erik’s Seven Summits itinerary:

- 27 Jun 1995: Denali/McKinley: Alaska, USA (North America) – 6,190 m (20,210 ft)

- 11 Aug 1997: Kilimanjaro, Tanzania (Africa) – 5,895 m (19,341 ft)

- 11 Jan 1999: Aconcagua, Argentina (South America) – 6,961 m (22,837 ft)

- 13 Jan 2001: Vinson (Antarctica) – 4,892 m (16,050 ft)

- 25 May 2001: Everest, Nepal/China (Asia) – 8,848.8 m (29,031 ft)

- 13 Jun 2002: Elbrus, Russia (Europe) – 5,642 m (18,510 ft)

- 5 Sep 2002: Kosciusko (Australia) – 2,228 m (7,310 ft)

- 26 Aug 2008: Puncak Jaya (aka Carstenz Pyramid), Indonesia (Oceania)* – 4,884 m (16,024 ft)

*The latter is an alternative highest peak for the region of Oceania, depending on where continental borders are placed

Erik’s hunger for adventure hasn’t stopped at rock climbing and mountaineering. Over the decades, he has also turned his hand to many other extreme sports, some of which others may have deemed impossible for someone without sight. These include running marathons, mixed-terrain cycling and solo kayaking. After several years training, the latter culminated in 2014 with a voyage of several hundred kilometres negotiating high-difficulty white-water rapids on the Colorado River through the Grand Canyon, accompanied by a guide in another kayak.

Erik kayaking the Colorado River in the Grand Canyon, with guide Harlan Taney. Credit: James Q Martin

Erik kayaking the Colorado River in the Grand Canyon, with guide Harlan Taney. Credit: James Q Martin

Another area where he is believed to have broken new ground is becoming the first blind person to solo paraglide in 2002. Though when pressed if he had any red lines or regrets when it came to adventuring, Erik confessed this was one area that he may have overreached.

“I paraglided independently for two years. I’d have people on the ground talking on radios, giving me directions, or on big jumps, there might be another paraglider on the flight. Eventually, I decided that solo paragliding was too risky.

“Despite what many people might think, I’m not a crazy adrenaline junkie. There are people that climb mountains who have this ‘I’m gonna risk everything for the success of this project’ attitude. I just don’t have that. I’m a wimp. So anyway, I quit paragliding because it just didn’t feel smart. You know that eventually something’s gonna happen.”

He’s been able to share the highs and lows of his groundbreaking adventures – as well as the can-do attitude that gets him through these challenges – via a plethora of motivational speaking engagements, books and documentaries.

Films of which he has been the star include The Weight of Water (2018) – which followed his unprecedented kayaking journey down the Colorado River – and Soundscape (2023) – a short focusing on Erik climbing a 1,200-ft (366-m) rock face called “The Incredible Hulk” in California’s Sierra Nevada Mountains. Both of these claimed top awards at the Banff Mountain Film Festival.

Erik on TV series Expedition Impossible in Morocco in 2011 with teammates Jeff Evans and Aaron Isaacson

Imparting his long self-practised mantra that any obstacle can be overcome with the right mindset was a key element of what drove him to co-found No Barriers in 2003. Established to help all people affected by disability – both those with the disabilities and those that support them – the charity organizes several mountain and backcountry expeditions each year to push people out of their comfort zone and hopefully make them reassess their strengths and capabilities. Erik told us how No Barriers was conceived: “After I climbed Everest in 2001, I got a call from Mark Wellman [the first paraplegic person to climb El Capitan, on 26 July 1989], who is one of my mountaineering heroes.

“He was doing a film project called Beyond the Barriers, which was this series of documentaries that highlighted disabled people doing crazy, cool things.

“He asked me to be a part of a film where we climbed this really cool tower out in the Utah desert called ‘Ancient Art’. I did that with Mark and also with double amputee Hugh Herr, who lost both of his legs below the knee to frostbite while climbing Mount Washington when he was 17.

Erik on a No Barriers expedition, assisting one of the adaptive explorers over some loose rock

“That trip was really the inspiration for No Barriers. I realized that people like this exist, living their best life, refusing to sit on the sideline.”

I was absolutely fascinated by the process behind someone’s life being shattered but then rebuilding it in a way to come back even stronger. How do you teach people to do that? And that’s what we try to do at No Barriers: give people a framework or roadmap that we call the “no barriers life” that will enable them to live more adventuresome, more fulfilling lives, whatever form that may take - Erik Weihenmayer on his inspiration for setting up his charity No Barriers

Given the huge difference that No Barriers has made to the lives of those who have engaged with its activities and ethos, are there plans to scale up the enterprise to reach a wider audience – or even to take it global? Erik feels that’s not the way they want to go right now. "It might not sound very ambitious but we just want to keep doing what we’re doing but constantly better. Our challenge is we take 15 veterans or 15 folks with disabilities out into the mountains for say a five-day expedition. It’s expensive work. It’s hard work. It takes a lot of preparation, a lot of energy and a lot of expertise.

“So realistically we’re not going to be able to scale up to thousands and thousands of people. Also, talk about scaling all the time sometimes backfires. So honestly we just want to keep changing lives, with a few people in a deeper, more transformative way.”

Erik during a skiing trip to British Columbia, Canada

Back to Erik’s own personal ambitions, for someone who has been there, done that and got so many T-shirts, can there be anything left to climb on his wishlist? It’s the sort of question you already know the answer to before it’s been asked.

“There are some massive north faces in the Dolomites I’d like to try. There are also some huge granite domes on islands near Rio in Brazil … the North Face of the Eiger always looms in my mind, although it's getting harder and harder to get the right conditions.

“So they’re not things like Everest that the whole world will know. But they’re things that other climbers will know.”

As a young teen, Erik was blown away by the likes of polar explorers Scott and Amundsen and mountaineers Norgay and Hillary, but couldn’t ever see himself among their ranks. But from GWR’s perspective, as we welcome Erik into the hallowed hall of GWR ICONs, he has more than earned his place among these intrepid pioneers.

In case you’re wondering what gets one of the world’s most hardcore adventurers through his arduous expeditions battling Mother Nature at her most savage and beautiful, you might be heartened to hear that Erik likes to get a takeout as much as the rest of us.

“My kids used to make fun of me because I love Thai food so much. I crave it all the time. So when I get home from a trip, I go straight to this take-out restaurant called Thai Gold and order a panang curry. My hot tub is also high on my priority list. Sometimes I’ll eat the Thai take-out while in my hot tub!”

And if eating a takeaway Thai curry in your hot tub isn’t the embodiment of the “no barriers” mindset, we don’t know what is.

Discover more record-breaking adventurers and sportspeople in this dedicated section.