Are vampires real? The cursed history of the largest vampire epidemic

Are vampires real?

There used to be a time when the question would have only one logical answer: yes.

Between 1725 and the 1750s, villagers in central Europe witnessed a mass hysteria frenzy that would later be known as the Great Vampire Epidemic, the largest vampire epidemic in history: killing several people, terrorizing thousands, and marking the rise of the vampire.

A brief history of vampirism

Instances of blood-sucking demons have plagued different civilizations since the dawn of time, from Persian folklore to the Romans empusae, beautiful but deadly female spirits who fed upon healthy young men. Recounts of vampire-adjacent myths can be found in China, or around the Norse undead spirit draugr.

However, we largely owe the archetype of the modern-day, sharp-fanged vampire to oral recounts from 18th-century Central Europe.

The modern term itselves derives from the Slavic “vàmpīr,” although the exact etymology is debated.

The word first appeared in the English language in the 1730s, possibly from German or French influences, in relation to the rampant epidemic that plagued Europe at the time.

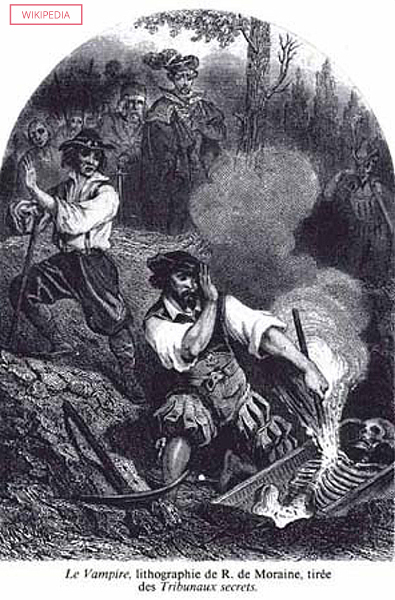

René de Moraine, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Similarly, the modern idea of revenants with long fangs and plagued by an unquenchable thirst for blood is rooted in 18th-century central European folklore, where communities became increasingly fearful of undead spirits rising from their graves.

For those villagers, the existence of vampires was a matter of survival.

The Great Vampire Controversy

The Great Vampire Epidemic (also known as the “vampire controversy”) represents history’s most widespread instance of vampire hysteria, extending primarily within the eastern and southern territories of the Austrian Empire from 1725 to the 1750s.

During these years, Austrian government officials and state physicians witnessed seemingly inexplicable deaths as locals tried to fight off the threat by exhuming, burning, and impaling the heart of the so-called vampires - the same people who had been their relatives, neighbours and loved ones in life - to stop them from feeding upon the living.

Historical records, diaries, and newspapers of the time documented over 30 cases of grave-digging.

However, it is likely that actual numbers largely surpass that estimate.

The epidemic’s origin can be traced back to the well-documented case of Serbian villager Peter Blagojovitch.

The 62-year-old man lived and worked in the area corresponding to modern-day Kisiljevo and passed suddenly in 1725.

Legend has it that the old man crawled out of his grave at night, walked among the living, and visited his son’s house asking for food. After he refused to feed the evil spirit, the son was found dead the morning after.

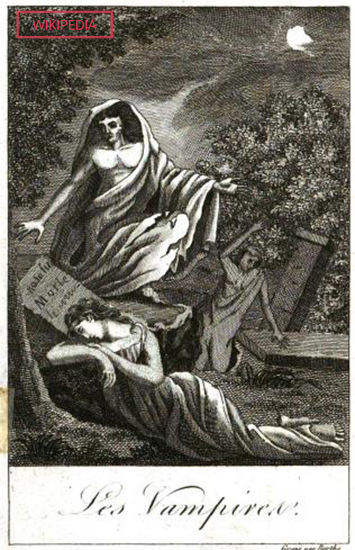

Berthe, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Berthe, Public domain, via Wikimedia CommonsAll victims perished within 48 hours of sudden illnesses and loss of blood, and Blagojovitch’s wife swore the ghost of her husband visited her asking for food (or shoes, in other versions of the tale).

In the end, burning Blagojovitch's corpse allegedly put an end to the mysterious deaths.

Garlic is believed to fight vampires

Garlic is believed to fight vampires

A similar case involved a Serbian infantry soldier named Arnold Paole.

A hajduk from Meduegna, Paole's death in 1725 caused an epidemic of vampirism that killed at least 16 people.

It all started after Paole passed away suddenly after breaking his neck during a fall: within a month of the tragedy, four people claimed to be plagued by his undead spirit – all of them falling ill and dying shortly after such claims.

That prompted the first vampire outbreak, which ended with Paole’s remains being exhumated and burned.

Records of the time claimed his body was undecomposed, sporting newly-grown nails and hair.

A second outbreak followed years later, in 1731, ending with 17 deaths and several corpses being excavated and destroyed.

Two Austrian military doctors were sent to document the case, and both Paole’s and Blagojovitch’s cases were discussed by officials, physicians, and eyewitnesses who later brought these disturbing stories back to Western Europe.

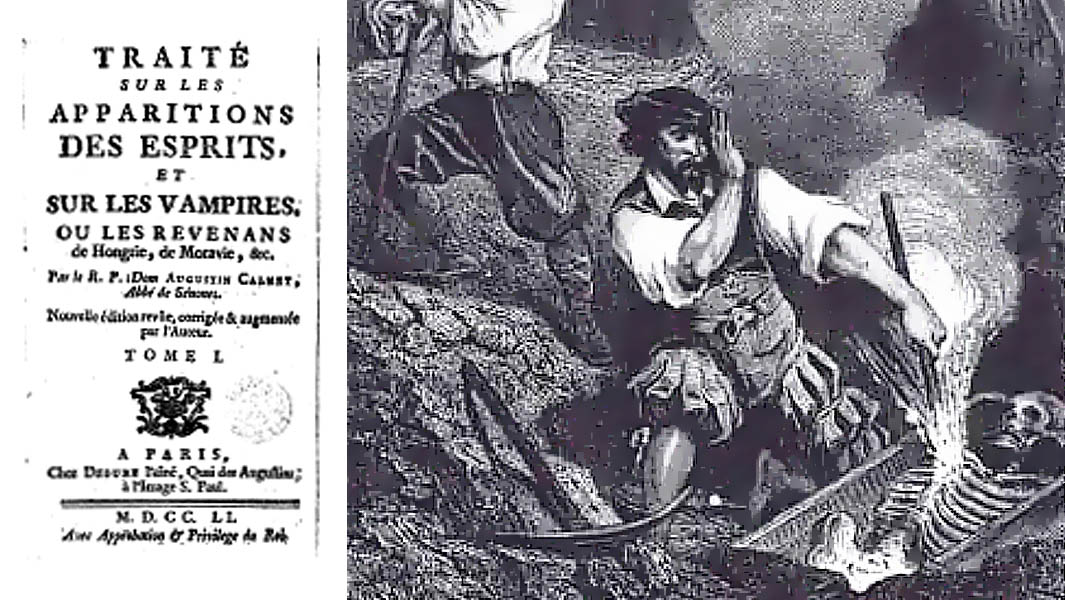

The controversy was also largely examined by contemporary critics and scholars, such as Antoine Calmet’s Treatise on the Apparitions of Spirits and on Vampires or Revenants of Hungary, Moravia, et al. (original title: Traité sur les apparitions des esprits et sur les vampires ou les revenans de Hongrie, de Moravie, etc).

The Benedictine monk first published his treaty in 1746 (later a two-volume dissertation was published in 1751) covering topics such as alchemy and witchcraft, vampires, and demonic presences.

He collected recounts of several vampire epidemics and testimonies, including the one of Arnold Paule, and reported the tragic tale of Stanoska, a young girl who died during the second outbreak of vampirism, in 1731.

Although the girl was in perfect health, she woke up screaming in the middle of the night and claimed she had been nearly strangled in her sleep by another victim of the outbreak, who had died nine days before.

She passed after three days of languor.

Later, the man was found with signs of vampirism: fresh blood and a lack of decay in the body.

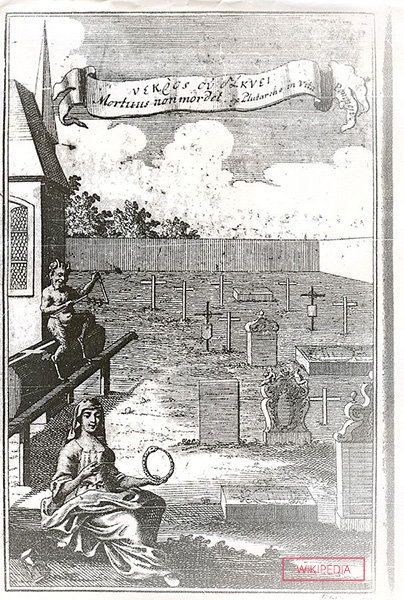

De masticatione mortuorum in tumulis

De masticatione mortuorum in tumulis

In his treaty De masticatione mortuorum in tumulis (or: On the Chewing of the Dead in their Tombs, published in 1728) Lutheran pastor and writer Michaël Ranft largely reported instances of cries and gnawing sounds souring from graves.

Some corpses had moved in their graves or displayed bite marks on their arms and coffins, as they had seemingly tried to devour everything within reach.

Likely, graves found with lids marked by claw marks and scratches could be explained as unfortunate medical mistakes. The ones described by Ranft could be tragic cases of people buried alive, rather than proving that evil spirits can rise from their graves.

Medical explanation

As religious anxiety and superstition fueled the waves of rampant hysteria that spread across Europe, most of the controversy seems rooted in misinterpretations of natural decomposition processes and (possibly) common illnesses.

A limited understanding of postmortem phenomena led communities to mistake apparent preservation of the body after death, spasms, bloating, and bleeding from the mouth as signs of vampiric possession.

Illnesses like tuberculosis, pellagra (although the disease was not well-known at the time of the Vampire Controversy, and it was first described in Spain in 1735) and rabies strikingly resemble symptoms traditionally associated with vampires.

Patients affected by rabies can exhibit violent hallucinations, fear of sunlight and aggressive behaviour, and the disease is circulated through human and animal bites.

Modern media

Despite its grim circumstances, the tales of evil spirits walking among the living contributed to a flourishing artistic landscape.

The early example of Polidori’s short fictional work The Vampyre (1819) is considered the precursor of a horror sub-genre and began a massive fascination with vampires, which evolved into masterpieces such as Le Fanu’s novella Carmilla (published in 1872) and Stoker’s 1892 genre-defining masterpiece Dracula.

Other historical figures further contributed to the vampire's fame, from the Hungarian countess Elizabeth Bathory, the most prolific female murderer, to Wallachia's famed Vlad III.

The voivode's cruel actions earned him the nickname "the Impaler" and famously inspired Stoker's Dracula.

Romania's Bran Castle is widely famous as Dracula's Castle. Interestingly, Vlad the Impaler never visited this fortress and it bears no connection with Bram Stoker's novel.

In contemporary media, the interpretation of vampires saw a considerable shift, evolving from real-life horrors to fictional catalysts to explore themes of immortality, anxiety, and fear.

Vampires became protagonists of a mass-media revolution, bagging central roles in games (like the videogame franchise Castelvania and the roleplay games of Vampire: The Masquerade) and in popular movies, as testified by 1979's cult hit Nosferatu The Vampyre and Bela Lugosi's iconic lead role in 1931 Dracula.

The 1997 drama series Buffy the Vampire Slayer made history with the largest TV budget for make-up, with a weekly average of $3,000 (£1,818) allocated for fake teeth, props, fake blood and contact lenses.

The final installment of the Twilight saga, Breaking Dawn Part II (USA, 2012), became the highest-grossing vampire film of all time in 2013.